|

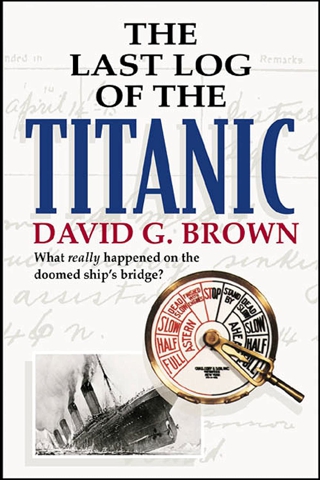

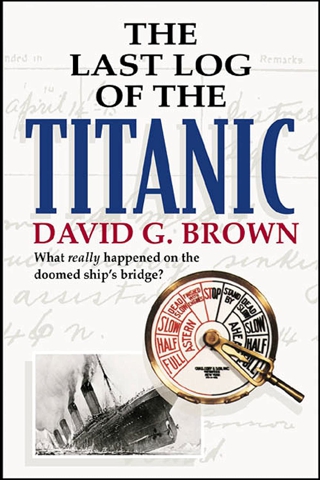

Among the many books about the Titanic (including an Eyewitness Book and even a Dummie's Guide), what is notably absent is an analysis of those ill-fated last hours not through the eyes of an historian or story teller, but through the lens of a mariner and ship handler applying accepted standards of seamanship--what is known to navies and merchant fleets as "the ordinary practice of seamen."

To our knowledge, this book is the first close look at the Titanic disaster by an author with the ship-handling background and knowledge to make an informed reconstruction of the ship's last maneuvers.

It gives book-length treatment to the final hours.

By contrast, Walter Lord's A Night to Remember covers the final maneuvers and the iceberg encounter in eight paragraphs.

These days, every airplane crash analysis begins with the effort to recover the black boxes recording final crew conversations and instrument readings.

Think how fascinating the black box from the Titanic would have been, but of course there was none.

On ships of that era as well as this one, the only "black box" was the ship's logbook, in which all weather observations, course and speed changes, and other relevant information were to be recorded.

To this day, a captain's best defense against charges of negligence is the official logbook.

But Titanic's logbook went to the bottom with the ship, and even if we were to recover it in readable condition, we would probably be disappointed with its coverage of events in the last hours.

The Last Log of the Titanic is a bold but careful reconstruction of the Titanic's final logbook entries.

It provides no startling new facts of the Titanic's sinking; rather, it's a fresh interpretation of known facts from a previously neglected point of view: the mariner's.

Some things that have been mysterious make more sense when viewed from this perspective (e.g., Captain Smith's treatment of the ice warnings and First Officer Murdoch's maneuvers immediately prior to the iceberg encounter).

Other things make less sense than ever.

Brown concludes that the ship did not actually collide with the berg, but grounded on a projecting underwater shelf;

that First Officer Murdoch almost pulled off a miracle of ship handling in those final minutes before the accident; that the ship, after the grounding, would probably have floated long enough for most or all passengers to survive if Smith hadn't resumed steaming, acceding to the demands of ship owner's representative Bruce Ismay;

that, because of this, there was inadequate time remaining to launch lifeboats even if lifeboat capacity had been adequate;

that surviving officers lied to and misled the American and British inquiries in order to protect their careers; and that the British Board of Trade had its own commercial and geopolitical reasons to bury the facts.

|