ANCRES HINGLEY NOAH & SONS

Encyclopedia Titanica

Titanic: The Hingley Anchors / Les Ancres de Hingley

The story of Titanic's centre anchor / Jonathan Smith / L'histoire de l'ancre centrale du Titanic

|

ANCRES HINGLEY NOAH & SONSEncyclopedia TitanicaTitanic: The Hingley Anchors / Les Ancres de HingleyThe story of Titanic's centre anchor / Jonathan Smith / L'histoire de l'ancre centrale du Titanic |

|

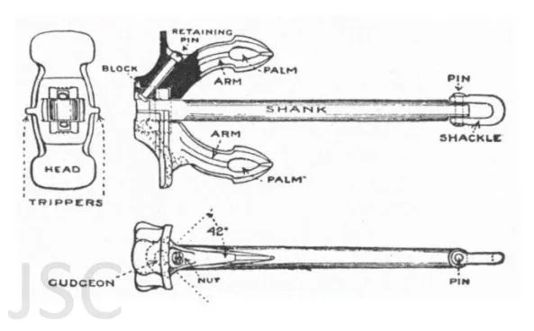

| The fabrication of the anchor shank was a much more daunting process. The shank would start life as a huge solid steel ingot formed from smaller blocks of iron bars and compacted into one large structure that would be more workable depending on size. Heated to over 5000 degree's in the furnaces, a 20 ton steam operated drop forge hammer was used to form the anchor shank’s principal shape. A team of workers known more commonly as Hammermen would in groups turn the shank using chain pulley system attached to the workshops roofing structure, sliding the heavy shank back and forth into the drop forged. Each time the steel began to cool, the section would be reheated in the furnace and the process repeated until the shank met to requirements in ordered size. The end result for Titanic's centre anchor was an object over fifteen feet in length and weighing almost 8 tons. For the eyelets at both ends of the shank, for the securing pins to be passed through to secure both head and shackle, the eyes were machine lathed and cleaned up. |

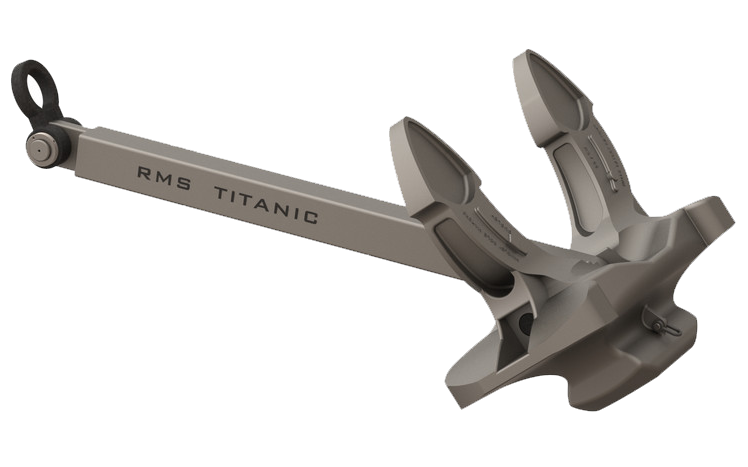

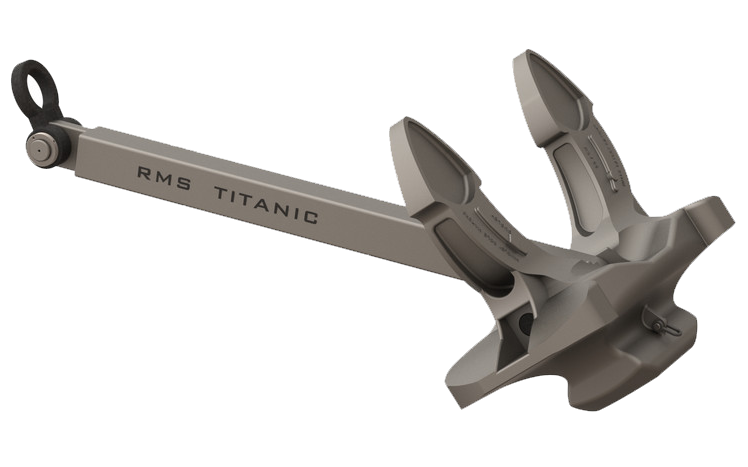

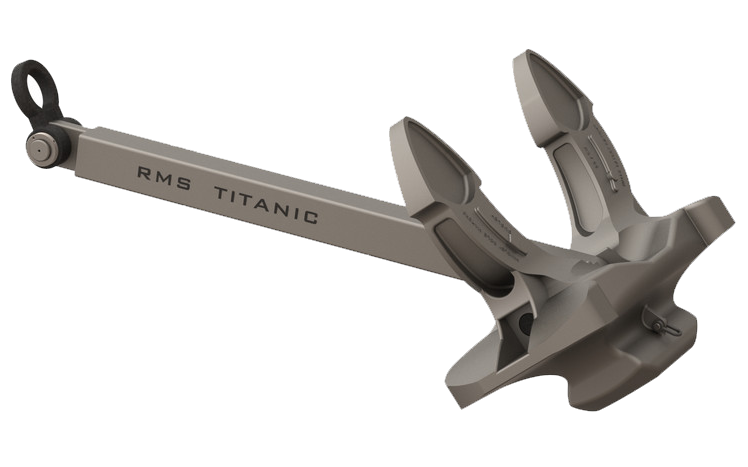

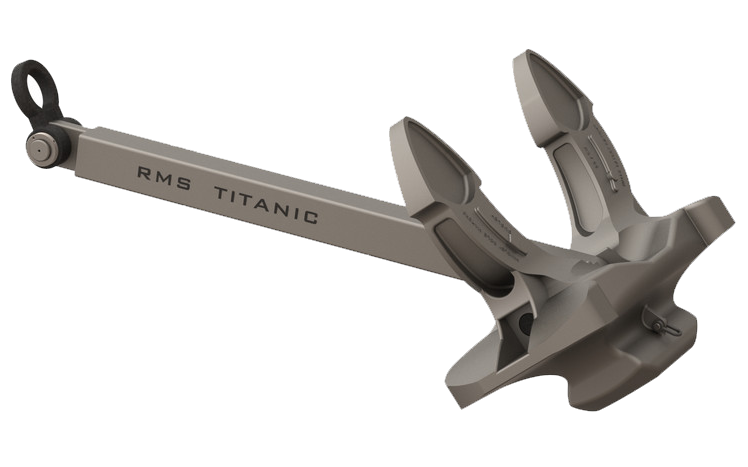

The 1910 Halls Olympic Class anchor. |

La fabrication de la tige d'ancrage a été un processus beaucoup plus intimidant. La tige devait d'abord être un énorme lingot d'acier massif formé à partir de petits blocs de barres de fer et compacté en une grande structure qui serait plus facile à travailler selon la taille. Chauffé à plus de 5000 degrés dans les fours, un marteau de forgeage à vapeur de 20 tonnes a été utilisé pour former la forme principale de la tige d'ancrage. Une équipe d'ouvriers, plus connue sous le nom de marteleurs, tournait en groupe la tige à l'aide d'un système de poulies à chaîne fixé à la structure du toit de l'atelier, faisant glisser la lourde tige d'avant en arrière dans le marteau de forgeage. Chaque fois que l'acier commençait à refroidir, la section était réchauffée dans le four et le processus était répété jusqu'à ce que la tige réponde aux exigences de la taille commandée. Le résultat final pour l'ancre centrale du Titanic était un objet de plus de quinze pieds de long et pesant près de 8 tonnes. Pour les oeillets situés aux deux extrémités de la tige, dans lesquels passent les goupilles de sécurité qui fixent la tête et la manille, les oeillets ont été tournés à la machine et nettoyés. |

| (1) Noah Hingley's Netherton Works (2) Lloyds Proving House (3) The dirt track leading to Northfield Road (4) Northfield Road. |

|

|

|

|

|

Noah Hingley & Sons |

Noah Hingley & Sons |

Noah Hingley & Sons |

© Joakim Amundsson |

© Joakim Amundsson |

© Joakim Amundsson |

Ancre de l'Olympic |

Ancre de l'Olympic |

Ancre de l'Olympic |

Ancre de l'Olympic |

Ancre de l'Olympic |

Réplique d'une ancre du Titanic |

Réplique d'une ancre du Titanic |

Réplique d'une ancre du Titanic |

Ancre du Britannic |

Ancre du Britannic |

|

|